Women’s visibility in science and academia

/This article is part of an ongoing blog series, titled Inequality in STEM: a Dive Into the Data. In this series, we cover recent research exploring and quantifying inequality in STEM. We'll discuss different aspects of inequality, including barriers to career advancement and a chilly social climate, as well as the efficacy of various interventions to combat bias. Our goal with these pieces is to provide clear summaries of the data related to bias in STEM, giving scientific evidence to back up the personal experiences of URMs in STEM fields.

While the number of women in science has been increasing for the last twenty years, women are still leaving scientific fields at all stages of their careers.[i] Research about the “leaky pipeline” suggests there is a disproportionate lack of female representation in crucial milestones for scientific career progression, such as receiving prestigious awards, publishing papers in important journals, and applying for patents.[ii] There are many ideas about why women continue to leave science as their careers progress, including differences in career goals and interests, parenting, differences in salary for equivalent positions, a lack of female role models and mentors, and explicit and implicit bias. Importantly, each of these factors contributes to a reduction in the visibility of women in science and academia.[iii]

But why does visibility matter? In their recent paper, Carter et al. explain how visibility can help determine whether women are interested in pursuing careers in science.[iv] As human beings, we look at the traits of people who occupy a field to determine what characteristics are needed to be successful in that field. If members of a certain group are overrepresented, we often assume that the traits required for success are found only in members of that group. When trying to determine our likelihood of being able to do something, we look to others with whom we identify, or who share a similar background (for women, these are other women). Thus, if women are not visible in science and academia, other women may think that they do not belong in or cannot be successful in those domains either.[v] Unfortunately, a leaky pipeline is a self-perpetuating problem: when women leave, their visibility is further reduced, which can lead to more women leaving, and so on.

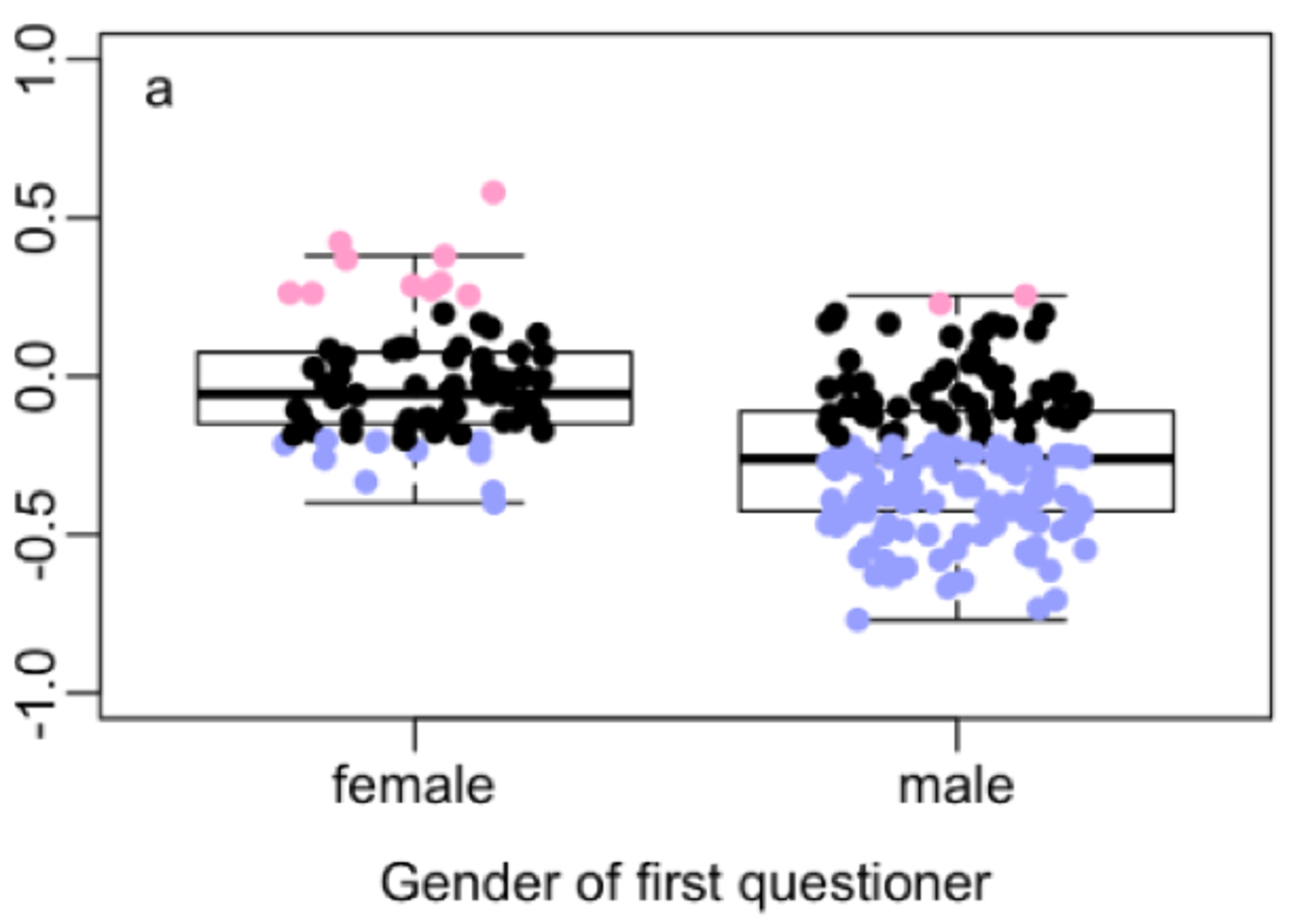

Carter et al. found that the gender of the first person to ask a question is a large contributor to the bias in question-asking behavior. In this figure, each point represents a seminar, and its color reflects the imbalance in question-asking. Black points represent seminars with little or no imbalance, pink points represent seminars where women asked disproportionately more questions than men given the gender ratio of the audience, and blue points represent seminars where men asked disproportionately more questions than women given the gender ratio of the audience. When a man asked the first question, the rest of the questions were likely to be asked disproportionately by men.

There are many ongoing efforts within the scientific community aimed at increasing the visibility of women. Research from Carter et al. and from another group, Sardalis and Drew,[vi] investigate two domains where women continue to be underrepresented and attempts to increase visibility could be particularly effective. Sardalis and Drew explored the first domain: visibility at international conferences. The authors collected information from ten years of conferences held by two different conservation biology societies. Their dataset included the number and the gender of conference speakers, organizers, and attendees, allowing them to assess the relationship between the number of female conference organizers and the number of female speakers who were invited to present their work. Their analysis revealed a significant, positive relationship between the number of female organizers and the number of female speakers, to the extent that increasing the number of female conference organizers by one corresponded to a 70-90% increase in the number of invited female speakers.

The second domain, examined by Carter et al., highlights a more common and frequent form of visibility: question-asking behavior at departmental talks and seminars. The authors observed 247 seminars held in biology and psychology departments at 35 different institutions in 10 countries. They found that men asked significantly more questions than women, after having taken into account the proportion of men and women in the audience. The authors then investigated what factors contribute to this imbalance, and found that the gender of the first person to ask a question had a large effect on the bias in further question asking. Questions were representative of the gender ratio of the audience if a woman asked the first question, but men asked disproportionally more questions if the first question came from a male.

Results from these two groups identify new potential avenues for intervention. Sardalis and Drew recommend that conferences try to increase the number of female organizers by providing opportunities and incentives. They also describe barriers preventing female participation at these events and detail actions that can reduce them, such as facilitating travel and providing subsidized childcare. Carter et al. recommend that speakers, teachers, and facilitators prioritize first questions from female attendees in local academic forums. Moderators can also prevent any one person from dominating a question period and increase the amount of time allotted for questions. Whether you are senior scientist implementing new policies at a conference or a graduate student teaching an undergraduate lab section, the findings from these studies and other research on bias in STEM can help us better design and target our efforts to increase the visibility of female scientists in academia.

[i] Lariviere, V., Ni, C., Gingras, Y., Cronin, B. & Sugimoto C.R. Global gender disparities in science. Nature 504, 211–213 (2013).

[ii] Hinsley, A., Sutherland, W.J. & Johnston, A. Men ask more questions than women at a scientific conference. PloS One 12, e0185534 (2017).

[iii] Ceci, S.J., Ginther, D.K., Kahn, S. & Williams, W.M. Women in Academic Science: A Changing Landscape. Psychol. Sci. Public. Interest 15, 75–141 (2014).

[iv] Carter, A., Croft, A., Lukas, D. & Sandstrom, G. Women’s visibility in academic seminars: women ask fewer questions than men. arXiv:1711.10985 (2017).

[v] Stout, J.G., Dasgupta, N., Hunsinger, M. & McManus, M.A. STEMing the tide: using ingroup experts to inoculate women’s self-concept in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100, 255 (2011).

[vi] Sardelis, S. & Drew, J.A. Not “Pulling up the Ladder”: Women Who Organize Conference Symposia Provide Greater Opportunities for Women to Speak at Conservation Conferences. PLoS One 11, e0160015 (2016).