Newsflash from 1976: neurons can release more than one neurotransmitter

/Neuroscience has a lot of mantras. I blame textbooks.

The concept of “one neurotransmitter per neuron” nicely streamlines any discussion of neuron types. The problem: it’s at best reflection of 80-year-old dogma, and a wild over-simplification. So the fact that evidence to the contrary is rarely found in textbooks should … not surprise you.

The 1930s gave us many things: instant coffee, trampolines, and most relevant to this post, Dale’s Principle, which states that, “the nature of the chemical function … is characteristic for each particular neurone, and unchangeable”. Although this assumption remains the default, co-release of neurotransmitters has been formally discussed (read: published about) since at least 1976. In the past decade, the idea that neurons can release more than one neurotransmitter has gained ever wider acceptance amongst neuroscientists, with the list of brain regions containing co-releasing neurons growing rapidly.

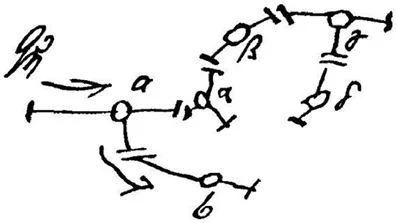

But what does co-release look like at the level of synapses? And why is there an image from my PhD qualifying proposal in this post?

Read More