We Cannot Address America’s Mental Health Crisis Without Addressing Anti-Black Racism

/For far too long, anti-Black racism has led to violence against the mental and physical well-being of Black Americans and has prevented equal access to healthcare. The dramatic rise of mental illness in the United States has had a disproportionate impact on Black and African American individuals. On a population level, Blacks in the US disproportionately experience higher psychological distress and lower well-being than whites, and tend to have more severe, long-lasting mental illnesses than whites. Suicide has also been on the rise for Black Americans, with the age-adjusted suicide rate for Black populations in 2018 accounting for approximately half of the overall U.S. suicide rate despite Blacks making up roughly 13.4% of the U.S. population. Recently, calls to alleviate the “mental health crisis” have coincided with renewed efforts to address systemic racism in the United States following the unjust murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and many others this year. With the confluence of these energies, we are well-poised to tackle these intertwined challenges with sustained vigor, but doing so will require us to take a hard look at the intersection of racism and mental health.

How does racism impact the mind and brain? David R. Williams, a scientist and professor at Harvard University, has been leading investigations into this question for many years. When faced with skepticism that racial discrimination could be accurately measured, he developed and validated the “Everday Discrimination Scale,” now the most widely used and well-accepted tool for scientists to measure the impact of discrimination on health. In addition to the well-documented effects of racism on a wide variety of physical health outcomes (higher infant mortality, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and shortened life expectancy, to name a few), studies using Dr. Williams’ discrimination scale have revealed that anti-Black racism in the United States also has serious impacts on mental health and wellbeing.

Recently, Dr. Williams published a summary of the scientific research on the mental health impacts of racism in populations of color. With Dr. Williams’ summary in hand, let’s talk about some of the ways that racism can impact mental health. First, we’ll discuss the broad effects of racial discrimination and internalized racism. Then we’ll discuss the impact of other factors contributing to poor mental health like mass incarceration and police brutality. Finally, we’ll touch on some important differences in access and quality of mental health care.

Racial Discrimination Affects Mental Health

Overt racial discrimination, which is the differential treatment of minoritized individuals, has negative impacts on various aspects of mental health. It’s associated with greater mental distress, increased mood and anxiety disorders, and a higher likelihood of being diagnosed with multiple mental disorders at once. One study even showed that the number of instances of discrimination that someone experiences is directly related to how much that person’s mental health declines over time.

How does racial discrimination lead to poorer mental health? Researchers have repeatedly shown that stress (both chronic and acute) and heightened vigilance are key risk factors for mental illness. When someone experiences racial discrimination on a day-to-day basis, they may become chronically stressed and hyper-vigilant. This state of stress and hyper-vigilance with racial discrimination is associated with sleep difficulties, poorer cardiovascular health, increased body weight, and depressive symptoms. Anticipating racial discrimination also heightens both physical and emotional stress responses. In one study, Latina individuals who anticipated an encounter with a potential perpetrator of racial discrimination showed heightened concern and feelings of threat before the encounter and increased stress and cardiovascular responses afterward.

“Racial discrimination begins early in life, with both direct and indirect impacts on children and adolescents.”

How early do the effects of racial discrimination set in? Unfortunately, research has shown that racial discrimination begins early in life, with both direct and indirect impacts on children and adolescents. Adolescents who directly experience racial discrimination themselves report more depressive symptoms, and when parents experience racial discrimination, their kids may also be negatively impacted. In addition to the impacts of direct racial discrimination against children, researchers have shown that parental exposure to racial discrimination increases children’s anxiety and depressive symptoms as well as their likelihood of substance use. Maternal discrimination, in particular, is associated with poorer outcomes for children’s social and emotional development. In general, poorer mental health in parents can negatively impact parenting behaviors also leading to poorer childhood development, which may be one way that the effects of discrimination are passed down through generations.

Internalized Racism Affects Mental Health

In addition to the many ways that overt racial discrimination can negatively impact mental health, systemic racism can also attack from within. Living in a society where racism and racial discrimination abound, it becomes easy to internalize racist ideas. All of us, even those of us who are discriminated against, hold subconscious racial biases and stereotypes that can inadvertently affect our attitudes and behaviors toward minoritized groups. Black Americans who have subconsciously internalized these pervasive negative stereotypes against Black people tend to have lower self-esteem and higher psychological distress. Multiple studies have shown that higher levels of internalized racism (stronger agreement with stereotypes about Black people) are associated with increased depressive symptoms.

A key factor here is that internalized racism tends to diminish self-esteem and self-worth, and some scholars think this is because racism diminishes an individual’s identity and sense of community belonging. It may even be the case that those with lower self-esteem are less likely to climb the social and economic ladder, making it more difficult to reach academic and career success, further perpetuating inequities.

Police Brutality and Incarceration Affect Mental Health

Any conversation about the disproportionate mental health impacts on Black Americans would be incomplete without discussing racism in policing and mass incarceration. In the United States, police kill more than 300 Black Americans each year, many of whom are unarmed. Compared with White Americans, Black Americans are three times more likely to be killed by police and five times more likely to be killed unarmed. In communities where unarmed Black Americans have been killed by police, studies have found elevated levels of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Police killings of unarmed Black Americans impact mental health at a national scale.”

Police killings adversely affect the mental health of many people, even outside of the victim’s family, friends, and community: a recent study showed that police killings of unarmed Black Americans impact mental health at a national scale. The extent of this mental health impact was severe, amounting to 55 million poor mental health days annually, on par with the number of days taken for diabetes. No negative impact on mental health was found for white Americans, or for police killings of armed individuals. Another study showed that encounters with police are more stressful for Black Americans, with more severe impacts on mental health. The researchers found that the frequency with which Black Americans are stopped by police, the intrusiveness and disrespect felt in these encounters, and the perception of injustice in the outcome of the encounter were all associated with mental health symptoms of PTSD and anxiety.

Mass incarceration of Black Americans also contributes to disparities in mental health, with consequences for families and communities of incarcerated individuals as well. Not only do incarcerated individuals experience poorer mental health, with limited access to treatment, but research has also shown that children of incarcerated parents have poorer school outcomes, increases in aggressive behaviors, and numerous symptoms of mental illness. This could potentially further contribute to the intergenerational impacts of racial discrimination discussed above.

Disparities in Mental Health Treatment

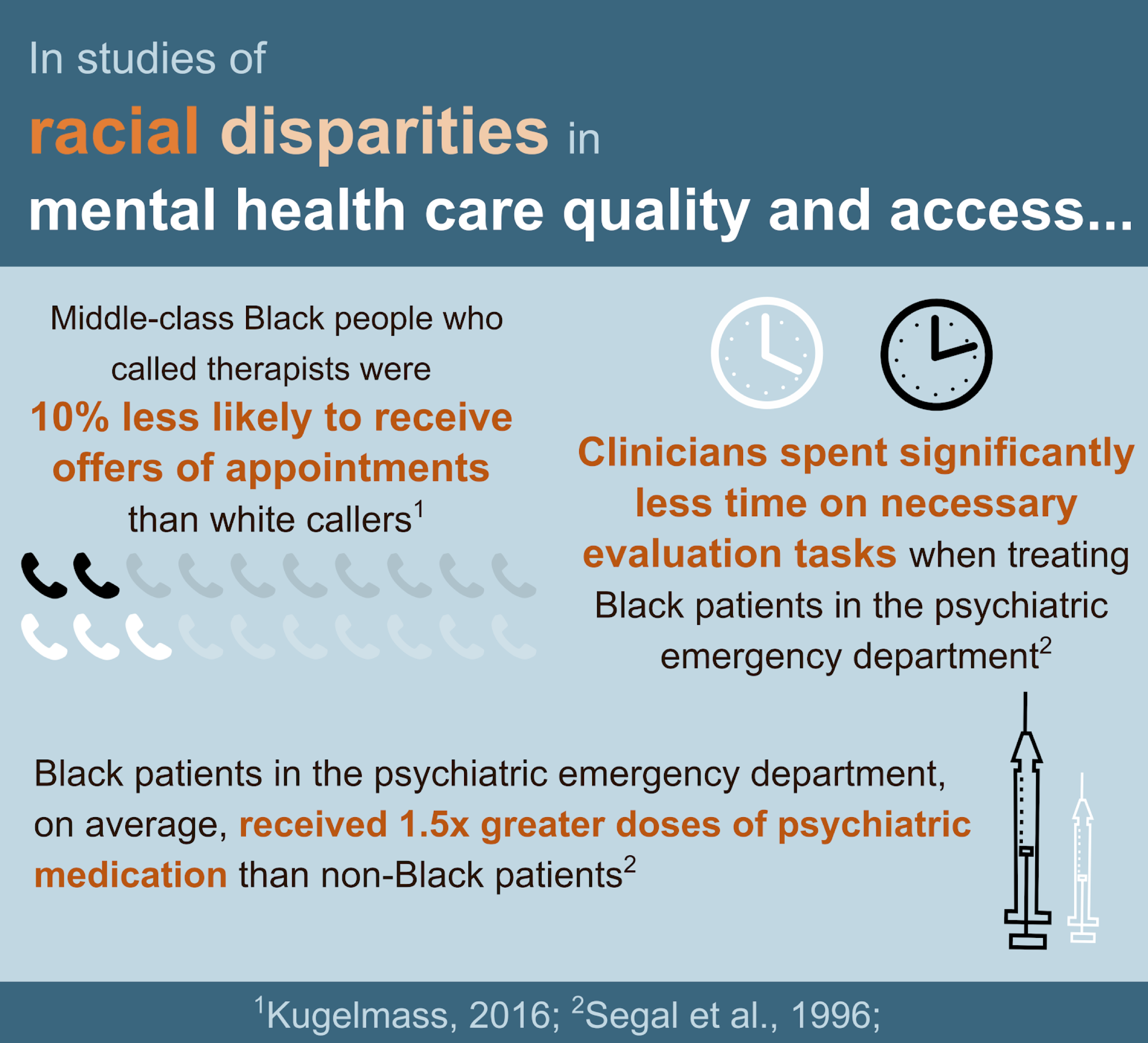

In addition to negatively impacting mental health, racism also imposes barriers and challenges when it comes to seeking and receiving mental health care. In a 2016 study, a researcher named Heather Kugelmass left 326 voicemails with licensed psychotherapists in New York City, each from a supposed patient seeking an appointment, with a racially distinctive name and voice (either Black or white). She observed that callers with Black names/voices were less likely to get appointments with the therapists than their white counterparts, which suggests that unconscious racism can pose a barrier to mental health treatment even after accounting for discrepancies in income level and insurance coverage.

There are also disparities in the ways that Black individuals receive mental health care. Clinicians tend to spend less time with their Black patients than their white patients when conducting evaluations, with a tendency to over-medicate Black patients with antipsychotics compared to white patients. This follows a long, well-documented history of Black individuals being over-diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Dr. Mia Moore Kirby, an assistant professor in social work and the Center for African American Studies at the University of Texas at Arlington, explains that Black women face particular challenges when it comes to seeking and receiving mental health treatment. The pervasive stigma against seeking mental health treatment that we’re all familiar with is amplified for Black women. “The 'strong black woman concept' (implies that) we're able to handle all things and so sometimes clinicians—who may not be culturally competent—may also speak that language,” she writes. When mental health care providers underestimate the pain and suffering of Black women, they are less likely to provide effective treatment.

Looking to the Future

“those closest to a problem are those closest to the solution”

Racism is violence against the body and mind. Whether by explicit discrimination or by the implicit and concealed racism woven tightly into our society’s threads, racism poses physical and mental health risks for Black individuals. To alleviate mental illness equitably for all people, we must be willing to look head-on at the evidence showing precisely how our unjust system operates and dismantle systems of oppression from the ground up. We must also be willing to adopt strategies that are guided by those at greatest risk. As Glenn E. Martin says, “those closest to a problem are those closest to the solution,” so marginalized individuals must be involved as scientists and policy-makers in designing solutions to the mental health crisis in America.

Senior Editor: Ashlea Morgan

Artwork By: Sedona Ewbank

Additional Resources on Race, Racism and Mental Health: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1AGLEOlNitQ1JI7MvQXZxrpEbAvr42r5RewjO_iXaKtE/edit#heading=h.m3e2itrhl9ci